32nd Annual Pre-Trib Study Group Conference

Sheraton Hotel, Irving, TX

December 4–6, 2023

Taking the Future Literally

The Importance of a Literal Interpretation of Ezekiel 40–48 to Biblical Hermeneutics

By Randall Price

Interpreting the Ezekiel’s prophecy has never been an easy task. The Talmudic rabbis struggled with the numerous textual difficulties and discrepancies from the Torah. Most decided that it was best to wait for the Prophet Elijah, at the final Redemption, to explain them (Babylonian Talmud, Menahoth 45a)! However, one named Rabbi Chanina ben Hezekiah accepted the challenge and sequestered in an upper chamber expended over 300 jars of oil in his lamps before successfully reconciling them. Had he not, we are told, the entire Book of Ezekiel might have been excluded from the Hebrew canon![1] Therefore, despite the difficulties presented by this book, and especially chapters 40-48, we must wrestle with it because with it we face the question of the literal interpretation of all the Bible. Indeed, these last nine chapters of Ezekiel serve as a test case for whether any Old Testament prophetic text related to Israel’s future restoration can be interpreted literally. Charles Lee Feinberg explains the importance of this when he writes:

Along with certain other key passages of the Old Testament, like Isaiah 7:14 and 52:13-53:12 and portions of Daniel, the concluding chapters of Ezekiel form a kind of continental divide in the area of Biblical interpretation. It is one of the areas where the literal interpretation of the Bible and the spiritualizing or allegorizing method diverge widely. Here amillennialists and premillennialists are poles apart. When thirty-nine chapters of Ezekiel can be treated seriously as well as literally, there is no valid reason a priori for treating this large division of the book in an entirely different manner.[2]

The most generally accepted interpretation of this prophecy by critical scholars is that it was understood by the post-exilic community as a spiritual ideal (never intended to realized literally) and fulfilled in their rebuilding of Zerubbabel’s Temple. Reform scholars and other non-futurists view these chapters as symbolic either of a spiritual entity such as the Church or the Church’s worship, Heaven, the eternal reign of God or the eternal state or the New Jerusalem. The hermeneutic used to accomplish this is the reading of the New Testament back into the Old Testament (especially the analogy of the Church to the Temple in Eph. 2:19-21 and the comparative description of the New Jerusalem in Rev. 21:1-22:5).[3] In this view, the New Testament is new (superior) revelation that reinterprets the old revelation to reveal its hidden message for the Church (cf. the concept of “better” in Hebrews understanding not simply that the fulfillment in Christ is “better,” i.e., superior to the promises concerning Him, but that this demonstrated a fulfillment theology showing the proper interpretation of the Old Testament types (especially concerning Israel), as subsumed in Christ the antitype.)

The Spiritual Vision Model Influenced a Non- Literal Interpretation

In the Spiritual Vision Model, heaven is seen as the place where believers in Christ are destined to live forever. It is a non-earthly spiritual place where believers will exist as spiritual beings engaging in spiritual activities. It is a realm of spirit and not of matter. This belief that the final dwelling place of Christians is in an ethereal heaven. Early church fathers, like Origen, a founder of the allegorical stream of hermeneutics, lived in Alexandria was influenced greatly by Plato and the Greek philosophers. Most of those who contributed to this model, like Augustine, were also influenced heavily by classical Greek philosophers. On the Jewish side, Philo Judaeus (Philo of Alexandria) followed Neo-Platonism to allegorize the Hebrew biblical heritage. This Greek philosophical bent toward the eternal and transcendent which superseded the changing material world produced a non-literal interpretation of Old Testament prophecy that has dominated Christianity for centuries. The hermeneutic developed from the Spiritual View Model prioritizes the New Testament (which it takes as a heavenly-oriented) and from this perspective re-reads and therefore reinterprets the Old Testament (which it takes as land-centered) from an assumed theological understanding that Jesus and the early Church transferred and transformed the fulfillment of restoration promises from National Israel as the old fleshly recipient to the Church, the new spiritual recipient.

An example of how this theological assumption based on the Spiritual Vision Model intrudes into literal historical research can be seen in George Athas (professor of Church History at Moore Theological College, Syndney, Australia) Bridging the Testaments: The History and Theology of God’s People in the Second Temple Period. After 388 pages of discussion on the political and religious events of the Second Temple period with the Jerusalem Temple as the most significant factor in Jewish history, the author moves to an excursus on “The Early Church and the Temple” in which he states:

The early church, however, saw Jesus’s vision being for a transformed people of God, transcending nation, land, and temple … Jesus demands the destruction of the old temple and the erection of a new one (John 2:19). This was not a call for the replication of the old system but a wholesale transformation … Jesus’s death was interpreted as a definitive sacrifice once for all time, obviating the need for ongoing sacrifice. The writer to the Hebrews, who wrote to Jewish Christians after the destruction of the temple in AD 70, argued against the need for a physical temple because of Jesus’s superior priesthood in accordance with the quasi-Platonic metaphysic of Jewish apocalyptic thinking … Jesus fulfilled the purpose of the old cult and rendered all subsequent earthly sacrifice defunct (Heb. 9:1-15) … This moved Jewish Christians away from the need for temple-based worship altogether by showing that Israel’s historic destiny had all along been a heavenly city without physical foundations (Heb. 11:10) – a heavenly Jerusalem (Heb. 12:22) reached by faith in Jesus. To turn back from this was tantamount to apostasy, akin to the rebellion of the Israelites who failed ultimately to reach the promised land (Heb. 3:16-4:11; 10:26-31) … it provided a theological mandate for graduating from Jerusalem-based temple worship.[4]

How can such an interpretation of early Jewish-Christianity incorporate and explain Paul, the foremost Jewish-Christian Apostle to the Greeks continuing to offer sacrifices in the Jerusalem Temple (Acts 21:21-26; 24:17-18) and to confess in his Roman trial that he had followed his ritual obligations to the Temple all of his life (Acts 25:8; 28:17; cf. 20:16)? Apparently, the Apostles Peter and John, who went to worship (including sacrifice) in the Temple (Acts 3:1-8) likewise had no understanding of the transformation and transferal that their Master had, according to this view, taught them.

Those who adopt the Spiritual Vision Model are predisposed to a spiritual interpretation of Old Testament (earthly) versus New Testament (heavenly) texts. They claim support for their view in the Book of Hebrews critique of Old Testament ceremonial ritual. Concerning this Jerry Hullinger notes:

The metaphorical view holds that the author is spiritualizing the cult in order to apply it to Christ, thus indicating the subjective benefits that accrue from His work. Therefore, everything spoken about loses its literal significance. In this view the literal priesthood is an analogy to speak of salvation, the heavenly sanctuary is the church, and the essence of sacrifice is not blood atonement but obedience. In this way of thinking Hebrews becomes an extended metaphor which is very much influenced (seemingly) by Platonic thought. In addition, it wreaks havoc with the literal correspondences between the sacrifices of the Old Testament and that of Christ.[5]

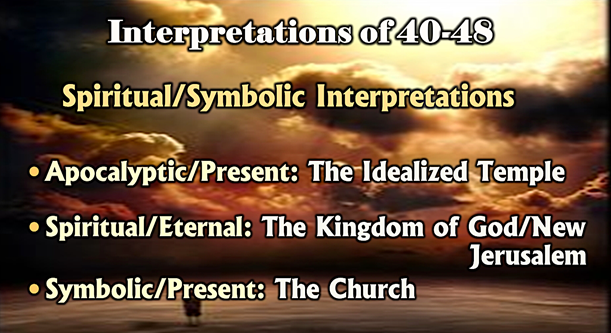

This spiritualizing principle is thought to have been the method employed by the New Testament writers in their use of the Old Testament and therefore the whole of kingdom preparation in the Old Testament must be understood as shadow giving way to substance. Karlberg argues in this vein when he writes: “In the eschatological age of the Spirit the kingdom of God is a spiritual reality unencumbered by the shadowy earthly forms (types) characteristic of the ancient theocracy.”[6] The dominance of the spiritual interpretation in the eastern and western churches and the denominations developed from (or in opposition to) them has made the literal interpretation of Dispensationalism appear as either extreme (US) or bizarre (UK). National Israel under the Old Covenant only existed as a failed experiment that allowed the spiritual remnant (the Church, the True Israel) to attain to the New Covenant. Since the legal and ritual systems under the Old Covenant were to yield to the spiritual grace system of the New, the idea of a literal fulfillment for the promises to National Israel had to be recast to symbolic or spiritual fulfillment for the Church. Ezekiel 40-48 as indicative of, if not a template for, the restoration of National Israel could only be understood as having apocalyptic fulfillment in the present as the idealized temple, spiritual fulfillment eternally in the Kingdom of God or the New Jerusalem or as a symbol in the present of the Church.

Although there are similarities with Ezekiel’s Temple and spiritual realities, for example in the description of the New Jerusalem as being built on a high mountain, having high walls and the abiding Presence of God there are significant differences (the description of the New Jerusalem far surpasses that of Ezekiel’s Temple) and similar abodes of God’s glory in the eschaton and eternal state would expect resemblances. However, if literal interpretation is rejected, in deference to the Spiritual Vision Model, then not only is there no portion of Scripture which supplies the instructions for the construction of the future Temple and its service and the way has been opened for the spiritualization of all of the restoration prophecies to Israel.

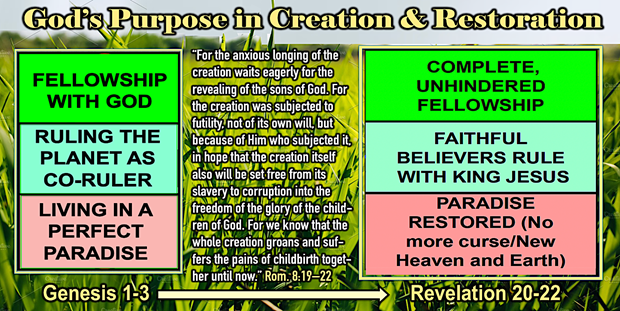

The New Creation Model Promotes Literal Interpretation

By contrast, the New Creation Model finds the fulfillment of the divine ideal of Eden in the new heavens and new earth of the millennium and eternal state.[7] This is supported by the Prophets’ statements of the New Covenant that declare God’s promises to national Israel are permanent and inviolable (Jer. 31:35-37; 33:20-26; cf. fulfillment in Isa. 61:4-7; 65:17-25; 66:18-23; Ezek. 37:25-28). Attached to the first and last statements of the New Covenant (Jer. 31:27-34; 33:1-19) these legal affirmations serve as the strongest sworn statements of the divine promise guaranteeing their eventual fulfillment for Israel. Thus, as the rules of nature exist and stand forever, so the sons of Israel will be God’s chosen people forever. As the correct orders of creation exist in His presence, so will the seed, that is descendants of Israel; both are permanent. This vindicates divine justice against the indictment of the nations that God could not fulfill His promises to His People (Ezek. 36:20). God had to act in judgment due to His attribute of justice (Amos 3:2) and to also act in mercy because of His attributes of immutability and love (Rom. 11:28-29, 31).[8]

The only way this undeniable national promise can be construed to not find fulfillment with national Israel is by a larger theological reinterpretation that transforms everything national (land-based) to spiritual (heavenly). On this basis, fulfillment is only with the Church as the intended recipient (the True Israel) or by inheriting the spiritual blessings originally given to national Israel as their spiritual replacement.[9] Advocates of this method of interpretation must view Ezekiel 40-48 within their schema and therefore argue that it precludes a literal fulfillment in history with National Israel.

Does Lack of Past Fulfillment Argue Against Literal Interpretation?

However, before considering arguments for a literal interpretation, the fact that history reveals Ezekiel’s Temple was never built by the post-exilic community has been used as an argument against taking the text as a literal plan to rebuild. Department Chair and Senior Professor of Old Testament Studies at Dallas Seminary Robert Chisholm, Jr. argues that normal literal interpretation cannot be supported here because the historical failure to rebuild demands a reinterpretation . He writes:

Ezekiel’s vision of a new temple and a restored nation was not fulfilled in the postexilic period. How then should we expect the vision to be fulfilled? Scholars have answered this question in a variety of ways. On one end of the interpretive spectrum are those who see the vision as purely symbolic and as fulfilled in the New Testament church. On the opposite end are the hyper-literalists, who contend that the vision will be fulfilled exactly as described during the millennial age. In attempting to answer the question, one must first recognize that Ezekiel’s vision is contextualized for his sixth-century B.C. audience. He describes the reconciliation of God and his people in terms that would be meaningful to this audience. They would naturally conceive of such reconciliation as involving the rebuilding of the temple, the reinstitution of the sacrificial system, the renewal of the Davidic dynasty, and the return and reunification of the twelve exiled tribes. Since the fulfillment of the vision transcends these culturally conditioned boundaries, we should probably view it as idealized to some extent and look for an essential, rather than an exact fulfillment of many of its features.[10]

First, there is no evidence in the post-exilic prophets that the post-exilic community upon their return to Jerusalem expected to rebuild the Temple according to Ezekiel’s plan. Why in exhorting the community to rebuild the Temple did they not repeat Ezekiel’s instructions since they were, in fact, God’s instructions? Rather, the post-exilic prophets indicate that rebuilding the Temple was not a priority,[11] and it is clear that when the community finally rebuilt they only followed the plan of First Temple. Even then, they were unable to duplicate that plan and its inferior form caused grief to those who had seen the original structure (Ezra 3:12). Therefore, there is nothing to suggest that Ezekiel’s design influenced the construction of the Second Temple under the priest Zerubbabel and Jeshua and their fellow priests and Levites (Ezra 3:2, 8; 5:2; Hag. 1:1, 14; 2:4; Zech. 4:9).

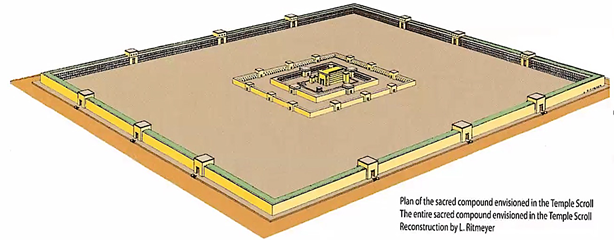

Second, there is the witness of the Jewish People during the Second Temple period that they interpreted the building of Ezekiel’s Temple plan as literal and reserved for the time of National Israel’s complete restoration to the Land and the Lord, something required in Ezekiel (36:22-37:28) but never experienced and still anticipated by the post-exilic prophets (e.g., Hag. 2:5-9; Zech. 8:3-23). The Second Temple Jewish community that provides us with this evidence is the Qumran Community that settled in the Judean desert near the Dead Sea ca. 150 BC in an earlier Iron Age settlement that had been abandoned in the Hellenistic period. Those leading this settlement are believed to have been Zadokite priests who were replaced in their duties in the Jerusalem Temple by Hasmonean priests after the Maccabean Revolt (167-164 BC). When their documents were discovered in the late 1940’s-50’s, among them was a document that been called the Temple Scroll (11Q19). Based on its date it preceded the Qumran Community and therefore may have been the product of the last generation of post-exilic Jews under the Seleucid dynasty. Possibly authored by a Zadokite priest, the Temple Scroll gives a plan for a future rebuilt Temple whose design was clearly influenced by that in Ezekiel 40-48.

The time in the future when this Temple is expected to be built is stated in the Temple Scroll:

And I will consecrate My [T]emple by My Glory (Shekinah), (the Temple) on which I will settle / My Glory, until the day of blessing (= the End of Days) on which I will create My Temple / and establish it for Myself for all time, according to the covenant which I have made with Jacob at Bethel.” 11QTemple 29:8-10

Notice in this passage that this Temple is to be built in the eschatological future (“Day of Blessing”) when the Shekinah Glory will return to Jerusalem (cf. Ezek. 43:1-7) and that this is expected to be the Temple that will stand for “all time.” Another passage expected that the Ark of the Covenant would be recovered and installed within this Temple (11Q19 7:10-12). In addition, Yigael Yadin, who did the initial research and publication of the Temple Scroll, concluded that it was a literal Temple for the eschatological age:

The author [of the Temple Scroll] was definitely writing about the earthly man-made Temple that God commanded the Israelites to construct in the Promised Land. It was on this structure that God would settle his glory until the day of the New Creation when God himself would "create my Temple … for all times" in accordance with his covenant "with Jacob at Bethel.[12]

There are other Dead Sea Scroll texts such as The New Jerusalem (4Q554; 55Q15) and apocalyptic works (included in the Dead Sea Scrolls library) such as Jubilees and 1 Enoch that also reveal a dependance on Ezekiel’s Temple plan but the Temple Scroll is sufficient to show that this Jewish sect understood a literal and eschatological interpretation of Ezekiel 40-48.

Further evidence that the post-exilic community understood a literal interpretation of Ezekiel 40-48 can be seen from the Samaritan temple built during the Persian period (ca. 450 BC).[13] The Samaritan ruler Sanballat, after being denied by the post-exilic leaders a part in building the Judean Temple (Ezra 4:1-5; Neh. 2:10; 4:1) constructed a rival temple on Mt. Gerazim. Based on the archaeological witness it has been thought that some of Ezekiel’s design features may have been employed in combination with those of the First Temple.[14] George Athas explains:

The sacred complex at the top measured approximately 96 x 98 meters and was surrounded by a dry-stone wall. Chambered gates in the northern, eastern, and southern walls led into an open courtyard with an altar at its center. The altar and courtyard lay directly before the sanctuary, which was approximately 40 meters by 20 meters wide, and stood in the central western part of the complex. The sanctuary was entered on its east side, with the Holy of Holies at its western end. While the configuration resembled other tripartite temple structures in the ancient Near East, it bore particular resemblance to both the Jerusalem Temple in Ezekiel’s day (Ezek. 8-11) and his idealized temple (Ezek. 40-48). This suggests that it was modeled upon Jerusalem’s temple and touted as its successor.[15]

If Sanballat indeed tried to incorporate some of Ezekiel’s design, it tells us that Ezekiel’s plan was clearly known to the post-exilic community.[16] What is pertinent to our discussion is that based on this detail from the archaeological excavation of the Samaritan temple it can be understood that Ezekiel’s Temple design was accepted literally.

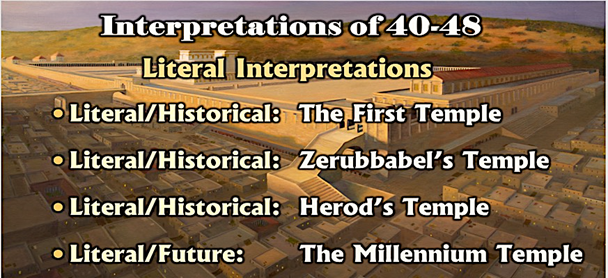

Literal Interpretation of Ezekiel 40-48

Biblical higher critics accept that Ezekiel had a literal structure in mind, but only with respect to a past temple (Solomonic, viewed as an ideal temple) or of a present temple in its former and latter constructions (the Zerubbabel or Herodian Second Temple). They argue Ezekiel’s grandiose description was hyperbolic with the intent of encouraging the post-exilic (not pre-exilic) community. Despite viewing Ezekiel’s Temple as an historical structure, their concept of an idealized or exaggerated design denies the literal understanding of the text’s description which cannot be successfully harmonized with any historical Temple (e.g., greater dimensions, elevated position and location in the Land, differences in ritual practice and priesthood, absence of sanctuary furniture, tribal arrangements in the Land). The only literal interpretation that respects the text in context is the future (eschatological) interpretation that understands fulfillment historically in the coming Millennial Age. This has been the historical interpretation of Orthodox (rabbinic) Judaism and argues that their predecessors in the post-exilic Jewish community realized fulfillment awaited the time of future restoration when all of the conditions of global spiritual and physical restoration (including the subjugation of the Gentile nations) had occurred.

Let us therefore consider seven arguments from Ezekiel 40-48 that will answer the critics objections and support the literal eschatological interpretation of this section of the prophetic word.

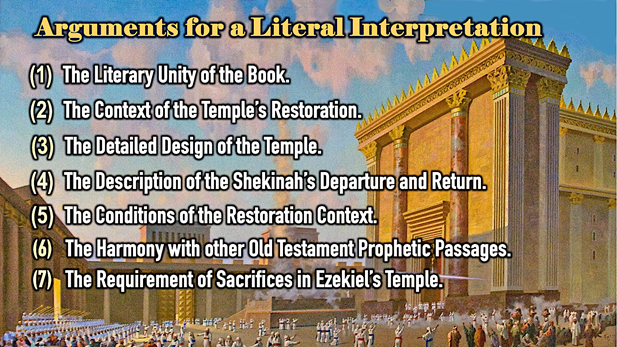

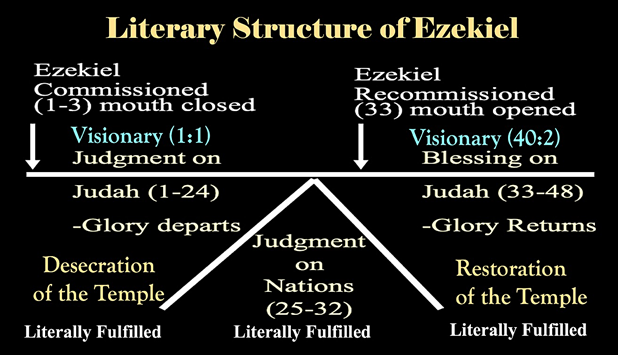

1) The Literary Unity of the Book Requires a Literal Interpretation Be Understood Throughout

Chapters 40-48 form an inseparable literary conclusion to the book. Although these chapters constitute a new vision in the prophecy, they are linked with chapters 1-39 in repeating earlier themes in a more detailed fashion. This linkage may be seen in the fact that the beginnings of chapters 1 and 40 share several similar features. For example, Ezekiel’s vision of the presence of God in Babylon (Ezekiel 1:1; compare 8:1) finds it complement and completion in the vision in the Land of Israel (Ezekiel 40:2). In like manner, the problem created by the departure of God’s Presence in chapters 8-11 finds its resolution with its return in this section (see Ezekiel 43:1-7).[17] In fact, the concern for the Presence of God could be argued as the uniting theme of the entire text of Ezekiel."[18] Without chapters 40-48 there is no answer to the outcome of Israel, no resolution to their history of sacred scandal, and no grand finalé to the divine drama centered from Sinai on the Chosen Nation.

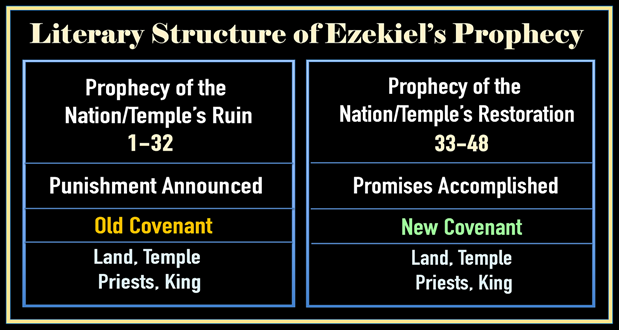

Ezekiel’s prophecy of the future Temple is the means to restoring the Presence of God to Israel. Its focus in the book falls into three divisions: (1) Prophecies of the Temple’s desecration and destruction (Ezekiel 4:1-24:27), (2) Prophecies of Israel’s return and restoration (Ezekiel 33:1-39:29), and (3) Prophecies of the Temple’s rebuilding and ritual (40:1-48:35). Since it was the physical First Temple whose desecration and destruction was discussed in the first section of the book, the last section’s discussion of a Temple’s restoration would also expect a structure of the same kind. In view of the exilic understanding of a return from captivity necessitating a rebuilding of the Temple (Daniel 9:20; 2 Chronicles 36:22-23; Ezra 1:2-11; Haggai 1:2-2:9; Zechariah 1:16; 6:12-15; 8:3), would Ezekiel (or God) have attempted to comfort his people’s loss with anything other than the literal restoration of a physical Temple to which the Divine Presence would return?

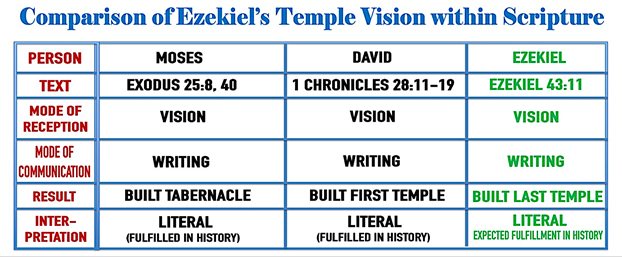

If it is countered that chapters 40-48 are a spiritual vision and therefore not meant to be a literal reality, again the literary structure of the book argues against this possibility. In chapters 8-11 all interpreters agree that the literal Solomonic Temple in Jerusalem is in view. Ezekiel’s description of its desecration is the basis for his explanation to the exilic community of why God would have to remove His Presence and destroy its structure. However, it must be remembered that Ezekiel was not physically present in Jerusalem when he reported these things, but in Babylon with the Judean exiles. Rather it was “in the visions of God” that he was spiritually transported to Jerusalem (Ezekiel 8:3). Everything he mentions there concerning the Temple, its “inner court” (8:3), “porch” (8:16), “altar” (8:16), “threshold” (9:3), and “East gate” (10:19), were all seen in a vision. Yet, they are considered to have been a vision of the literal Temple. Why then, when in a vision of the Temple (Ezekiel 40:2) in chapters 40-48 he mentions the exact same places: “inner court” (40:27), “porch” (40:48), “altar” (43:18), and “East gate” (43:3), are they now only spiritual symbols? Moreover, Moses saw the plan for the Tabernacle in a vision (Ex. 25:8, 40) as did David for the plans of the First Temple communicated to his son Solomon (1 Chr. 28:11-19), and no one contests that these “visions” were built literally in history. It is inconsistent to accept these “visions” as fulfilled literally but to argue that Ezekiel’s “vision” must be interpreted symbolically.

To summarize this point based on the literary unity of the book: If the visionary description of the First Temple and the prediction of its destruction is deemed historically accurate and, as all interpreters acknowledge, was literally fulfilled literally (Ezek. 24:2; 33:21; cf. 2 Kgs. 25:9; 2 Chr. 36:19; Neh. 2:17; Jer. 39:8; 44:6), why would not the same details and the prediction of its rebuilding not also expect literal fulfillment? If Judah and Jerusalem’s destruction and exile was literal, though described in a vision, why should not it restoration from exile and rebuilding (Ezek. 36-37; 40-48) not be understood as literal.

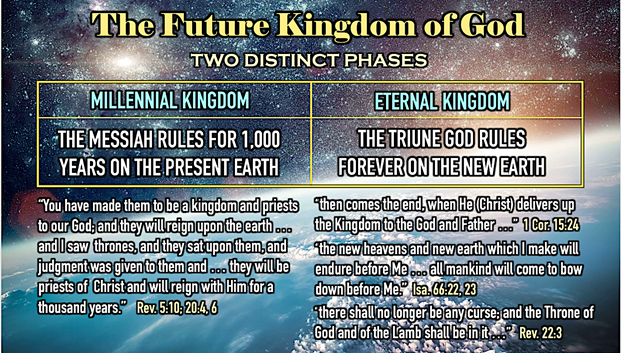

2) The Context of the Temple’s Restoration Requires a Literal Interpretation

These chapters open with a contextual note concerning the specific date of Ezekiel’s vision on “the tenth of the month [of Tishri]” (Ezekiel 40:1). The Jewish Sages saw this as already setting an eschatological context since the tenth of Tishri is reckoned as a Jubilee year [Hebrew, yovel], and the date of Ezekiel’s vision was determined to be the first Day of Atonement [Hebrew, Yom Kippur] of the Jubilee year. Together, this date prefigured Israel’s Day of Redemption in both its physical (Land) and spiritual aspects as Rabbi Joseph Breuer notes: “On that day, which summoned the subjugated and estranged among God’s people to accept freedom and called upon all the sons of Israel to return to their God, on that day it was given to the Prophet to behold a vision of the rebuilt, eternal Sanctuary of the future and to receive the basic instructions for the establishment of the State of God that would endure forever.”[19] Therefore, from the very first verse the Rabbis considered the context both literal and eschatological. If, as the New Creation Model affirms, the goal of the Creation is a renewal of man and earth so the two fulfill the co-regency of the Creation Mandate within a Theocratic Kingdom (see Rom. 8:19-24 and on the New Earth in the Eternal Kingdom (Eternal State). Since this goal requires God dwelling with His Creation (Psa. 68:16; 132:13-14; Ezek. 37:26-28; 43:7, 9; 48:35; Zech. 2:10; 8:3; Lk. 13:28-29; 22:29; Rev. 5:10; 11:15; 20:6; 21:3) an earthly Sanctuary is required. However, the eternal dwelling of God with man on earth is reserved for the future eschaton. Therefore, Ezekiel’s Temple can only have its construction within the eschatological context of the present earth during the Millennial Kingdom when the Messiah returns to reign for the thousand years (Matt. 25:31; Rev. 20:4, 6).

Daniel had also predicted that the Temple would be reconsecrated in the future as the climatic fulfillment of six eschatological restoration goals (Dan. 9:24). The reconsecration of Ezekiel’s Temple by the restored Presence of God appears as the climatic event in the restoration context of Ezekiel 37:25-28, which serves as an introductory summary of chapters 40-48: “And they shall live on the Land that I gave to Jacob [Israel] My servant, in which your fathers lived; and they will live on it, they and their sons’ sons, forever; and David My servant shall be their prince forever. And I will make a covenant of peace with them; it will be an everlasting covenant with them. And I will place them and multiply them, and I will set My Sanctuary [Hebrew, Miqdash] in their midst forever. My dwelling place [Hebrew, Mishkan] also will be over them; and I will be their God, and they will be My people. And the nations will know that I am the Lord who sanctifies Israel, when My Sanctuary [Hebrew, Miqdash] is in their midst forever.”

These verses reveal that the future restoration of the Nation will be in the same place (Israel) and in the same form (a Temple) as the past. The geographical context for this prophecy is “the Land that I gave to Jacob My servant, in which your fathers lived….” The mention of Jacob, who name was changed to “Israel” (verse 25), along with the historical habitation of “the fathers,” distinguishes this place as unquestionably the Land of Israel. Notice, too, the covenant made between God and Israel is “a covenant of peace …” (verse 26). No such covenant of security and well-being (the idea of the Hebrew shalom translated here as “peace”) was ever made with God during any time in Israel’s past, nor will it be made during the Tribulation period (the covenant of Daniel 9:27 is not stated to be a “peace covenant”). According to Ezekiel 34:25-29 this covenant is Land-centered, completely eliminating harmful animals, guaranteeing security from any foreign invasion, and bringing unparalleled agricultural renewal accompanied by divinely-sent seasonal rains (compare Zechariah 14:17). In addition, this covenant, unlike those of the past, is said to be “eternal.” This restoration of ethnic Israel, an event predicted by Paul (Rom. 11:25–32), can only be eschatological since history reveals that the northern tribes never returned to the land and disappeared as they were assimilated into the surrounding culture. Ezekiel’s vision of national restoration will be fulfilled only through the Jewish people, who are descended from Judah, Benjamin, and Levi (Ezek. 37:15–28; cf. Isa. 11:13–14; Jer. 31:31–37). This the first phase of restoring Creation to the Divine Ideal (redemption of man/world to reflect God’s image).

Ezekiel’s Temple Can Only be an Eschatological Temple

The Temple is here described in terms that can only be realized in the future. First, the Temple is called a mishkan, the Hebrew word used formerly for the Tabernacle and said to be “over them” (Hebrew, ‘lyhm).[20] This pictures God’s “sheltering Presence” as once the pitched Tabernacle in the wilderness protected the Israelite tribes. One of the false hopes of the past was in the inviolability of the Temple and its ability to preserve the disobedient Nation simply because it existed. In the future, however, the Nation will not sin and the Temple, with the Shekinah, will serve as the source of the Nation’s, and the world’s, prosperity and peace. The Temple is also called miqdash “Sanctuary,” emphasizing its holiness, and is said to be, like the covenant and the restoration of God’s Presence, “eternal” (verses 26, 28). Again, such a Temple could only find its fulfillment in the Millennial Kingdom where the protective “Glory-cloud” of God will return to fulfill this concept of the Temple (see Isaiah 4:5-6). This Temple, presented as part of the eternal covenant, in is that which is expanded upon in greater detail in the prophecy of chapters 40--48.[21]

As Professor Moshe Greenberg of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem explains:

The fivefold repetition of “forever” stresses the irreversibility of the new dispensation. Unlike God’s past experiment with Israel, the future restoration will have a guarantee of success; its capstone will be God’s sanctifying presence dwelling forever in the sanctuary admidst his people. The vision of the restored Temple (and God’s return to it) in chapters 40-48 follows as a proleptic [anticipatory] corroboration of these promises.[22]

Based on the nature of the promised restoration as revealed in Ezekiel 33-37, the returning exiles surely must have recognized that the nature of Ezekiel’s future Temple in chapters 40-48 was also eschatological. Therefore, those who rebuilt the Temple after the Babylonian Captivity did not attempt to implement its architectural design or priestly instructions. Their assessment of the kind of restoration they were experiencing had to be weighed against several factors: (1) The larger proportion of the Jewish population had chosen to remain in Persia and Egypt, (2) Only a paltry 49,897 Jews had returned to Judah (Ezra 2:64-65), and (3) the low level of spiritual life evident among the resident Jewish in the Land (Ezra 5:16; 9:1-4; Haggai 1:2-6). These realities must have indicated that their return and rebuilding was not the fulfillment of the final restoration described in Ezekiel. This was probably most apparent when the foundation of Zerubbabel’s Temple had been laid and the older people wept because it did not measure up to Solomon’s Temple (Ezra 3:12-13; Haggai 2:3), much less that envisioned by Ezekiel. Therefore, it must have been understood that Ezekiel’s Temple awaited the more complete promise of restoration which included the coming of the Messiah (Ezekiel 34:11-31), a full regathering of the entire Jewish Remnant (Ezekiel 36:24, 28), and a national spiritual regeneration (Ezekiel 36:25-27; 37:1-14). If Ezekiel’s readers were interpreting his restoration program for the eschatological age, then they would understand the interruption of Ezekiel’s “Gog and Magog” battle (Ezekiel 38-39) between the discussions of the Temple in chapters 37:25-28 and 40-48. This literary placement not only helped the readers understand an eschatological context for the Temple prophecy, but added the assurance that, unlike the foreign invasions of the past, even this greatest of foreign invasions in the future could not disturb God’s plans for the final Temple.

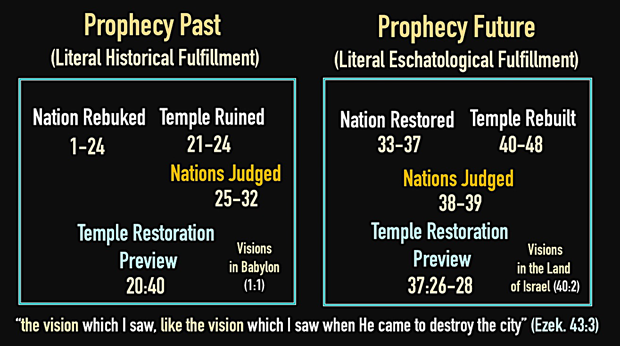

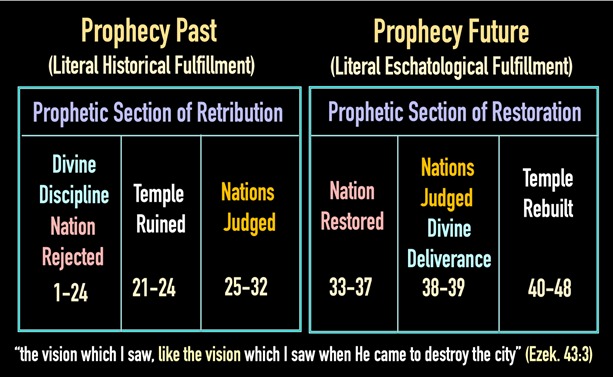

In Ezekiel’s literary scheme this is demonstrated with sections of Gentile judgment in the past (chs. 25-32) and future (chs. 38-39), the Nation rebuked (1-24) and restored (33-37), and the Temple ruined (chs. 21-24) and rebuilt (chs. 40-48). This literary structure displays the eschatological motif of desecration and restoration so common to the Prophets. In Ezekiel both sections are visionary but require that just as the sections of rebuke and ruin were fulfilled historically and literally, so must the sections of restoration and rebuilding.

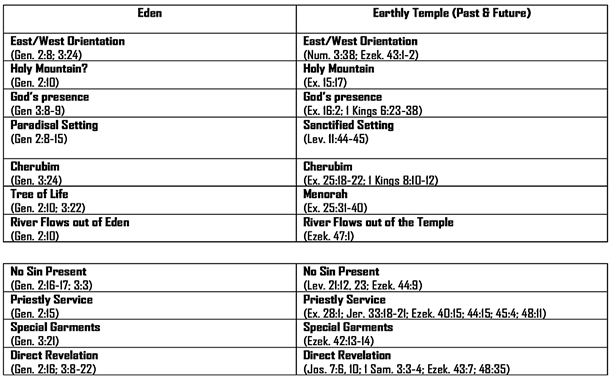

Theologically, we understand with the New Creation Model that in the Millennial Kingdom Ezekiel’s Temple fulfills the divine ideal that was created in the Garden of Eden with man as a sinless co-regent (Gen.1:26-28) and priest (Gen. 2:15) with a localization of the Divine Presence (Gen. 3:8) in the western part of the Garden, which appears to have constituted an earthly sanctuary.

3) The Description of the Shekinah’s Departure and Return Requires a Literal Interpretation

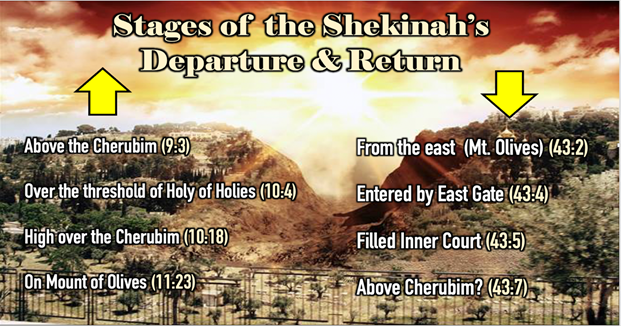

In Ezekiel’s prophecy of the desecration and destruction of the First Temple he gives a detailed picture of the progressive withdrawal of the Shekinah and its abandonment of the Sanctuary. While this may be thought to have been a symbolic and spiritual act, the description of the arrival of the Shekinah in 1 Kings 8:10-11 and 2 Chronicles 7:1-3 indicates that it was quite literal and visible. Therefore, when Ezekiel 43:1-7 details the return of the Shekinah to the rebuilt Temple, it cannot be understood in terms other than in the earlier context of Ezekiel and in harmony with the texts in the historical books. Moreover, this cannot be said to have been fulfilled in any other Temple, for nowhere in Scripture (nor in extra-biblical Jewish literature) is it stated that the Divine Presence filled the Second Temple as it did the Tabernacle (Exodus 40:34-35) and the First Temple (1 Kings 8:10-11; 2 Chronicles 5:13-14; 7:13). Rather, Jewish sources made a point of its absence (see Tosefta Yom Tov) and relegated such a hope to the eschatological period known as “the period of restoration of all things” (Acts 3:21). Considering the text of this prophecy in Ezekiel we read: “Then he [the angelic guide of 40:4] led me to the gate facing toward the east [Eastern Gate]; and behold, the Glory of the God of Israel was coming from the way of the east. And His voice was like the sound of many waters; and the earth shone with His glory … And the Glory of the Lord came into the house [Temple] by the way of the east. And the Spirit lifted me up and brought me into the inner court; and behold the Glory of the Lord filled the house. Then I heard one [God] speaking to me from the house, while a man [the angelic guide] was standing beside me. And He said to me, “Son of man, this is the place of My throne and the place of the soles of My feet, where I will dwell among the sons of Israel forever. And the sons of Israel will not again defile My holy Name …” (Ezekiel 43:1-7).

Note here that Ezekiel presents the return of the Shekinah in a precise reversal of its departure detailed in chapters 9-11: Departure: Holy of Holies to Inner Court to Eastern Gate to east; Return: east to Eastern Gate to Inner Court to Holy of Holies. The order intentionally matches so that Israel is able to realize the fulfillment of complete restoration, which heretofore lacked the decisive final act of the restoration of the Divine Presence. Note, too, that this return fulfills the Divine ideal of the Creator dwelling with His creation first shown at Eden and then at Mount Sinai. In this respect note the elements of God’s approaching Presence in the Garden of Eden (compare Genesis 2:8; 3:8) are repeated: an eastward orientation (verses 2, 4) and the sound of God’s voice verse 2), and the reference to “the Glory of the God of Israel” (verse 2) reminding the reader of His original return (the Tabernacle in Sinai) and of His prophetic promise to return His Glory (in the same way) to the Final Temple (Haggai 2:5, 7, 9). The last aspect of this description that confirms this is the future Messianic Age is that the “sons of Israel” will be not be able to again defile the Temple as in the past (verse 7). This will be because they have been constitutionally changed to prevent this possibility (Ezekiel 36:25-27; 37:14, 23). In summary, the literal Presence of God left a literal Temple (Ezek. 9-11). Since it was promised to return in exactly the same way to exactly the same place (Ezek. 43:1-7) this future fulfillment must be in a literally rebuilt Temple.

While the support for the Millennial Temple does not depend on this prophecy alone, it is the major text preserving the details for implementing its construction in the Millennial Kingdom.

4) The Conditions of the Restoration Context Requires a Literal Interpretation

In Ezekiel 43:18 the Prophet states the time for the rebuilding of the Temple and the installation of its ritual elements, such as the Brazen Altar. The text reads: “Son of man, thus says the Lord God, ‘These are the altar’s statutes on the day (בְּיוֹם הֵעָשׂוֹתוֹ) it is built …” This “day” (time) is understood in the context of this text (as well as other restoration texts) by specified conditions:

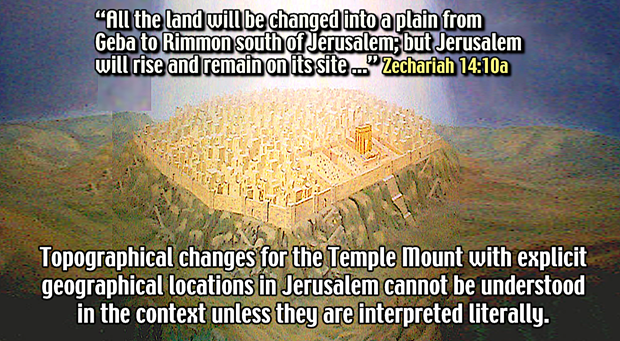

- Topographical dimensions - high mountain (Ezek. 40:2; cf. 20:40-44; Zech. 14:10)

- Israel’s national repentance (Ezek. 43:10-11; cf. 36:31-32)

- Israel national regathering and regeneration (Ezek. 43:7b; cf. 36:21-31; 37:4-14)

- Restoration of Zadokite priesthood (Ezek. 43:19; cf. 44:15-16)

These conditions require an eschatological fulfillment with National Israel within Israel’s covenant Land. However, additional conditions in the larger restoration context of Ezekiel’s prophetic section further support the time of the fulfillment of Ezekiel’s recorded vision.

The Description of the Restoration Land

The consecration of Ezekiel’s Temple by the restored Presence of God appears as the climatic event in the restoration context of Ezekiel 37:25-28. It serves as an introductory summary of chapters 40-48. These verses reveal that the future restoration of the Nation will be in the same place (Israel) and in the same form (a Temple) as the past. The geographical context for this prophecy is “the Land that I gave to Jacob My servant, in which your fathers lived….” The mention of Jacob, who name was changed to “Israel” (verse 25), along with the historical habitation of “the fathers,” distinguishes this place as unquestionably the Land of Israel. Notice, too, the covenant made between God and Israel is “a covenant of peace …” (verse 26). This covenant is Land-centered, completely eliminating harmful animals, guaranteeing security from any foreign invasion, and bringing unparalleled agricultural renewal accompanied by divinely sent seasonal rains (Zech. 14:17). No such covenant of security for the Land was made with God and Israel during any time in the Nation’s past nor will it be made during the Tribulation period. Moreover, this covenant is stated to be “eternal.” The only possible time for a literal fulfillment is the Millennial Kingdom, a time in which Israel as a Nation is restored to its Land in peace.

The Description of the Restoration Temple

The Temple is described in terms that can only be realized in the future. It is called a mishkan; the Hebrew word used formerly for the Tabernacle and said to be “over them.” This pictures God’s “sheltering Presence” as once the pitched Tabernacle in the wilderness protected the Israelite tribes. One of the false hopes of the past was in the inviolability of the Temple and its ability to preserve the disobedient Nation simply because it existed. In the future the Nation will obey and the Temple, with the Shekinah, will serve as the source of the Nation’s, and the world’s, prosperity and peace. The Temple is also called miqdash “Sanctuary,” emphasizing its holiness, and is said to be, like the covenant and the restoration of God’s Presence, “eternal” (vss. 26, 28). Such a Temple could only find its fulfillment in the Millennial Kingdom where the protective “Glory-cloud” of God will return to fulfill this concept of the Temple (cf. Isaiah 4:5-6).

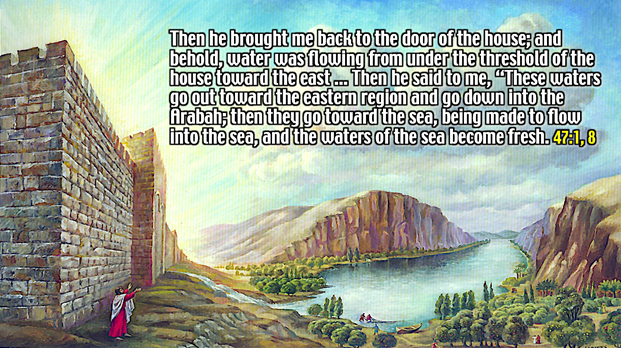

Another unique element of this future Temple is found in Ezekiel 47:1-12 where a river of water flows from under the threshold of the Temple from the right side south of the altar (vs. 1), then descends eastward producing fruit trees along its banks, and finally to the Arabah where it will merge into the Dead Sea, causing its waters to become fresh and sport many kinds of fish but leaving its swamps and marches salty (vss. 2-12).

Critics argue that this imaginative account is evidence that the whole of Ezekiel 40-48 is to not be taken literally. Against the critics on this point Merrill F. Unger has replied:

Keil insists that the marvelous river issuing from the temple cannot be regarded "as an earthly river," but can only be interpreted figuratively, and from this false premise concludes that therefore neither the temple, nor the ritual, nor the division of the land can be construed as literal. That the river is a literal stream, and that the temple mount will be exalted on a high eminence as the result of vast physical changes in the topography of Palestine is emphatically stated by others besides Ezekiel. Isaiah (35:1-10; 40:3-5) and particularly Zechariah are emphatic on this point (Zech. 14:4, 5). Only unbelief and blatant infidelity can wrestle with these Scriptures as presenting geographical impossibilities. God can do all that is necessary to revamp and remake the land of Palestine to make it a suitable scene for all the glorious events of the Kingdom Age.[23]

The Description of the Restoration Tribal Allotments

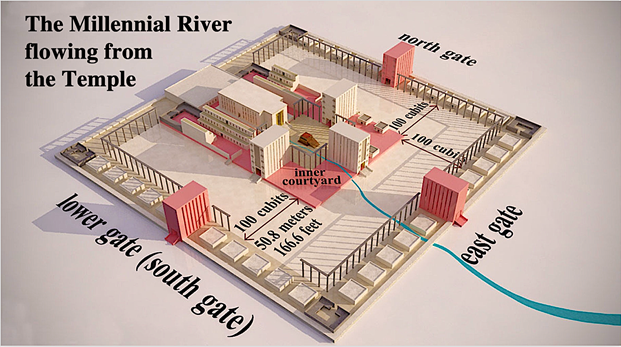

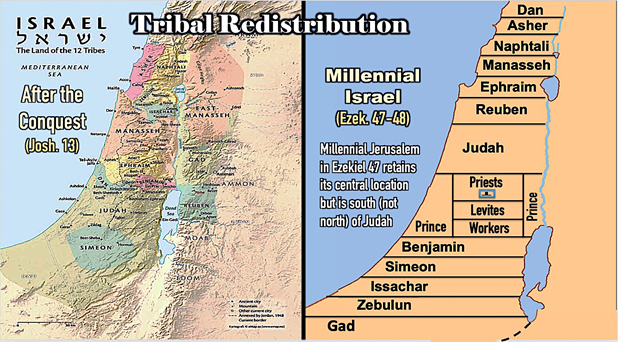

The twelve tribes of Israel, having been regathered, re-identified, reunited, and restored to the Lord and to the Land will be re-distributed by tribes within the boundaries of the Land. The seven northern tribes will be separated from the five southern tribes by the holy portion upon the Millennial mountain with its elevated city of Jerusalem and Temple. The northern tribes are allotted their inheritances (48:1-7). Moving from the north to south these include Dan (verse 1), Asher (verse 2), Naphtali (verse 3), Manasseh (verse 4), Ephraim (verse 5), Reuben (verse 6), and Judah (verse 7). The central portion of the Land (48:8-22) contains the Millennial mountain, with the precise location now revealed as south of the borders of the tribe of Judah (verse 8).

In the middle of the northern division of the holy portion on the mountain is the Millennial Temple (verses 10, 21). This holy portion (verses 12-15) also contains the Millennial Jerusalem in the southern division that will be laid out as a square of 4,500 cubits (7,875 feet) covering an area of 2.2 square miles (verse 16). The Millennial Jerusalem will have lands around it 250 cubits wide (437.5 feet) wide and on either side land measuring 10,000 cubits (3.3 miles) long and 5,000 cubits (1.65 miles) wide (verse 18a). This land is under the control of workers (who live in Jerusalem but who come from all the tribes) and is designated for agricultural purposes in order to feed the working population (verses 18-19). This mention of physical consumption reminds us (along with those in 36:9-11, 29-30, 34-36; 47:12) that the renewal of nature in the Millennial Kingdom is for the purpose of cultivation, production, and enjoyment of food. The holy allotment in this central portion will be the exclusive possession of the tribe of Levi (Zadokite priests and Levites) and its facilitator, the prince (verse 22). The allotment of territory to the five southern tribes (48:23-29) is described with respect to their borders, again from north to south, for Benjamin (verse 23), Simeon (verse 24), Issachar (verse 25), and Gad (verse 27). It should be noted in this discussion that Jesus promised His disciples who had followed Him that they would judge these twelve tribes in the Millennial Kingdom (Matthew 19:28).

The Description of the Restoration City of Jerusalem

When the Millennium begins topographical changes will occur in and around the city of Jerusalem to create the Millennial mountain which will be elevated above the hills (Isaiah 2:2) as all of the surrounding land will be flattened into a vast plain (Zechariah 14:10). This will be done so that the site of the Lord’s residence with His people occupies the highest situation in the region (hence always visible to the Nation). This will also result in the holy district with the Millennial Temple and Millennial Jerusalem becoming the new center of the Land (Isaiah 2:2; Micah 4:1). The symbolic school finds the immense dimensions ascribed to the Millennial mountain and its holy portion (Temple and city) proof that Ezekiel 40-48 cannot be interpreted literally. However, given such extensive topographical expansion, the new boundaries and dimensions are quite realistic.

The Millennial Jerusalem will have twelve gates named after Jacob’s (Israel’s) sons each measuring 4,500 cubits (2.2 miles). On its northern side (verse 30) the three closest to the Millennial Temple (verse 31) will be named for the tribes of Reuben, Judah, and Levi, perhaps reflecting Reuben’s firstborn status (Genesis 35:23), Judah’s past position as the site of the Temple (Genesis 22:2; Exodus 15:17; Deuteronomy 12:5-6; 2 Samuel 7:10), and Levi’s priestly position (Numbers 3:6). On its eastern side (verse 32) the gates will be named for Joseph, Benjamin, and Dan. As in Revelation 7:8, Joseph represents his sons Ephraim and Manasseh (Genesis 48:1) who were adopted by Jacob (Genesis 48:5-6). The tribe Dan is again distinguished, confirming that its past history will not prevent its future inheritance (see above). The gates on the southern side (verse 33) will be named for Simeon, Issachar, and Zebulun, whose tribal location in the south (48:24-26) meant that each tribe faced the gate bearing its name. On the western side (verse 34) the gates were named for Gad, Asher, and Naphtali.

Some commentators have criticized the seemingly narrow and parochial vision of Ezekiel that focuses almost exclusively on the Land and people of Israel. It appears as though God has returned only to Israel, whose people are alone mentioned having access to the Sanctuary and whose Temple-sourced river refreshes only the native ground. But it must be remembered that the vision came to Ezekiel while he was in exile with Israel and that his message of comfort was directed to the covenant people at a time when the nations were largely estranged from the God of Israel (cf. Ephesians 2:11, 19). If Ezekiel directs his prophetic hope of restoration to Israel, it is also because this promise was made to Israel in its covenant with God (Jeremiah 31:31-33). The election of national Israel has always been a problem to Universalists and replacement theologians, but Ezekiel’s vision should serve as a corrective that God has and will continue through the Millennial Kingdom, to mediate His blessings through His Chosen People (Genesis 12:3; cf. Romans 11:12, 15). However, Ezekiel has not been unconcerned about the fate of the nations, as the constant reminders that God’s intervention for Israel is a witness that He is the Lord (35:15; 36:23; 37:28; 38:23; 39:6, 7). At any rate, there are other prophets who have informed the nations of their promised place alongside Israel as a “blessing in the midst of the earth,” “My people,” and “the work of My hands” (Isaiah 19:23-25).

The fact of theophany distinguishes this Jerusalem from any other Jerusalem in history. The return of the Shekinah will signal the city’s restoration to the divine ideal and usher in the era of its promised blessing. While the Divine Glory will fill the Millennial Temple (43:7a) the extent of the glory on the entire Millennial mountain is such that the Millennial Jerusalem is also made glorious as “the throne of the Lord” (Jeremiah 3:17). According to Isaiah 4:5-6 the whole area of Mount Zion will be covered by the Glory-Cloud as a canopy (literally chupa, like the canopy over the Jewish wedding party) giving brightness by night (verse 5) and shade by day as well as protection from storm and rain (verse 6). This will also provide an independent light source for the city that will illumine it both day and night (Isaiah 24:23; 60:19-20). For this reason the city will be without walls, for the Lord will be a wall of fire around it (Zechariah 2:4-5), and its gates will be open day and night (Isaiah 60:11). This describes the security of God’s Land, which unlike former times, no longer requires protection, because the Lord is with His people and has restored fortunes of Israel with the nations (Zephaniah 3:15b-16, 20). The restored glory of Jerusalem is such that it can no longer be thought of without reference to the reality of God’s Presence. Therefore the name of the city will be renamed “the Lord is there” (Hebrew YHWH Shammah), verse 35b. Jerusalem has had many different names in the past: Ur-Shalem, Salem, Zion, Ariel, Aelia Capitolina, Al-Quds, but this will be its final change in name, for the Lord who defines it will never depart. In a similar way, the character of the city will also be reflected in its being referred to as “the Lord our Righteousness” (Hebrew YHWH Tzidikenu), Jeremiah 33:16, and “the City of Truth” (Hebrew ‘Ir Ha‘emet), Zechariah 8:3.[24] This divine presence will also endue the city with perpetual holiness (Zechariah 14:20-21). For this reason, the tribal allotments have been arranged so as to make the centrality of the Temple a literal, spatial, reality, rather than simply a theological notion (as the symbolic school contends).

5) The Description of the Temple’s Construction Design Requires a Literal Interpretation

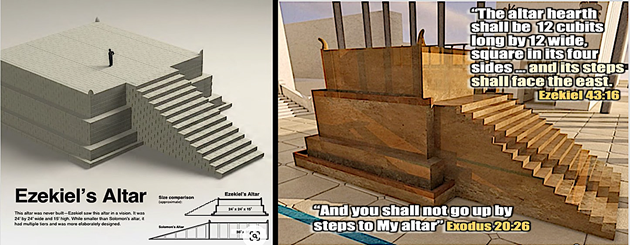

Even though the Jewish Sages found the description of the Temple in these chapters to be daunting, they all accepted it as a literal Temple to be built in the period of Israel’s restoration. As one commentator on this section stated: “These chapters are difficult to read without some attempt to draw what Ezekiel describes. Ezekiel was given specific instructions to “declare all that he saw to the house of Israel" (40:4). This is unnecessary if the Temple were to symbolize only general truths.

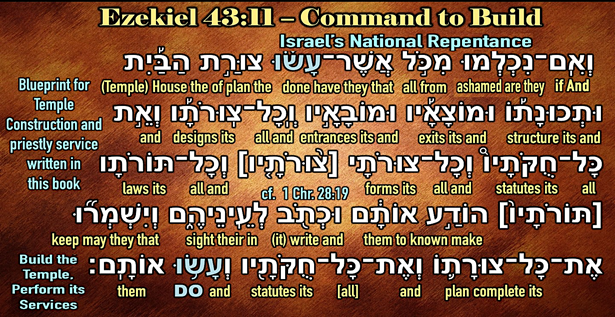

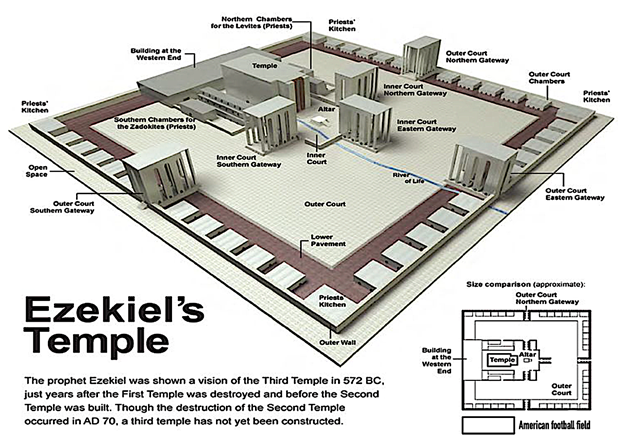

The detailed measurements invite the reader to sketch out this Temple plan, which, in fact, is what Christian and Jewish exegetes have done throughout the ages.”[25] Maimonides called it "the temple that will be built" and other Jewish scholars explained the design details including Rashi, David Kimhi, Yom-Tov Lipmann Heller, and Meir Leibush ben Yehiel Michal. They all attempted to produce varying sketches of Ezekiel’s Temple structure based on the 318 precise measurements given for rebuilding the Temple (Ezekiel 40:5-42:20). These measurements employ some 37 specific architectural terms that have no discernable connotation other than their normal and natural sense. Although the details seem tedious and repetitious, they are of fundamental importance to those who have been committed with the task of building this future Temple and performing its sacred service (43:10-11). They provide a glimpse into the mechanics of a regulated and orderly sacred society that will characterize God’s future Kingdom and remind us that the same God who gave this design to Israel also provided similar detailed instructions for the sanctified management of the local church (1 Cor. 14:25-49). Just as the local church follows literal instructions given by the Apostles for its operation, so the future Temple was provided literal instructions by the Prophet for its construction and maintenance. This is the impression the average reader has when reading of the Temple’s measurements, structures, courts, pillars, galleries, rooms, chambers, doors, ornamentation, vessels, priests, and offerings. Nevertheless, one of the leading commentators on the book has contended: “the description of the temple is not presented as a blueprint for some future building to be constructed with human hands,” and that “nowhere is anyone commanded to build it.”[26] However, in Ezekiel 43:10-11 we read: “As for you, son of man [Ezekiel], describe the Temple to the house of Israel … and let them measure the plan. And if they are ashamed of what they have done, make known to them the design of the house, its structure, its exits, its entrances, all its design, all its statutes, and all its laws. And write it in their sight, so that they may observe its whole design and all its statutes and do them.” These verses indicate that those Jews who live in the time of the fulfillment of Ezekiel’s prophesied restoration are to build the Temple. Later in this context (43:13-27) when the same kind of architectural measurements and detailed instructions are given for the altar, it is stated that it will be built by “the house of Israel” (verse 18). If the altar of the Temple is to be built, why not the Temple itself? This is in fact the case, for it is this same “house of Israel” to whom Ezekiel is commanded to “declare all that you see …” (Ezekiel 40:4).

This command in Ezekiel 43:11 to “observe its whole design and all its statutes and do them” is parallel in expression to God’s original command to build a Sanctuary given at Mount Sinai in Exodus 25:8-9. Moses was shown a vision of the Heavenly Temple (Ex. 25:9, 40) and instructed to literally build a copy of it on earth (Ex. 25:8). In like manner, David was given a vision of the design for the First Temple and all of its furniture and utensils and instructions for the priests and Levites, which he gave to Solomon (1 Chr. 28:11-19). If the house of Israel interpreted the earlier vision to Moses and David and their consequent building the Tabernacle and First Temple and the establishment of the priesthood literally, why would they not likewise interpret the same with respect to Ezekiel and God’s command to them? It is exegetically and theologically inconsistent to deny to Ezekiel an interpretation accepted in Exodus and Chronicles.

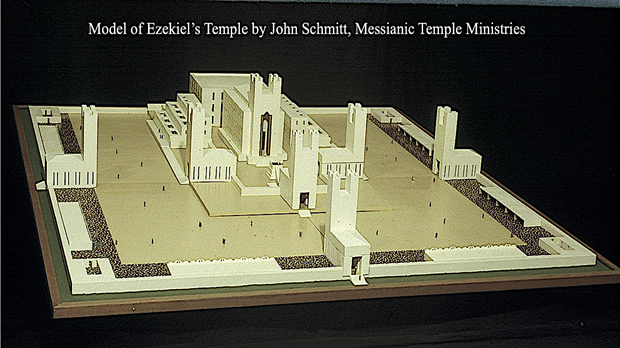

If we consider the detailed description of the Temple, we discover that the plans communicated to Ezekiel are so precise that blueprints could be drawn and a building constructed from them when conditions permitted. In fact, a physical three-dimensional model of this Temple has already been made by John Schmitt, the Executive Director of Messianic Temple Ministries[27] and numerous other digital reconstructions can be found online.

When a comparison is made between the details for the construction of the Temple buildings and the sacrificial system in Ezekiel and those recorded elsewhere for the construction of the Tabernacle and First Temple and their service, there is no reason to take them as less literal or historical. Would Ezekiel have been given such elaborate and practical instructions if only spiritual or symbolic realities were intended? Would the house of Israel be expected to interpret them in any manner other than that which was consistent with God’s revelation of previous structures, especially in the absence of any guidelines for an alternate (symbolic) interpretation?

Although it is possible that symbolical and spiritual significance can be discovered in the details of the Tabernacle and Temple’s construction and ceremonies, it is interesting that such symbolism is not directly revealed in the Bible. Of course, there is an analogous use of ritual language in relation to the spiritual service of the believer (Romans 12:1-2; 1 Corinthians 3:16-17; 6:19) and of the Spirit-filled Church (Ephesians 2:21-22), but this is not the same as typology where a type is fulfilled by an antitype. Even in a book such as Hebrews, in which a comparison is made between Israel’s liturgical system and the believer’s gracious access in Christ, and where such a symbolic significance might be expected, only a description of the Tabernacle and its furniture is given (Hebrews 9:1-5). This passage does refer to the “outer Tabernacle” as a “symbol” (or “figure,” “illustration”) [Greek, parabole] for “the present time” (verses 8-9). The interpretation of these verses are much debated,[28] but their main point is that the Levitical system was weak in that it offered only limited and exclusive access to God’s Presence. But, as one writer has noted, “This does not mean that the Levitical system was bad or that it did not accomplish the purpose for which God instituted it.”[29] However, even if the Scriptures were replete with symbolical and spiritual uses of the entire Levitical system with its Sanctuary, this would in no way affect their literal interpretation. John Whitcomb, long time professor of Old Testament at Grace Theological Seminary, makes this point when he says:

The fact that its structure and ceremonies will have a definite symbolical and spiritual significance cannot be used as an argument against its literal existence. For the Tabernacle was a literal structure in spite of the fact that it was filled with symbolic and typical significance. Such reasoning might easily deny the literality of Christ’s glorious Second Coming on the basis that the passages which describe His coming are filled with symbolical expressions (see Matthew 24 and Revelation 19).[30]

Therefore, even if one could impute symbolic meaning to the Temple and ritual descriptions in Ezekiel 40-48 (although in the Old Testament there is no precedence for this and in the text no guide for understanding the symbolism), there is no reason why the fulfillment should not be as literal as for every Temple and priesthood of the past.

6) The Harmony with other Old Testament Prophetic Passages Requires a Literal Interpretation

The same text that commands the house of Israel to build the Temple also states the time when they are to build it: after “they are ashamed of all that they have done” (Ezekiel 43:10-11). The time of this national repentance accords with the eschatological period previously described in the restoration text of Ezekiel 36:22-38 in which Israel has been made “ashamed” as part of the regenerative work of the Spirit (Ezek. 36:30-33; cf. Zech. 12:10-13:1). Just because the exilic community expected restoration does not mean that what they experienced upon their return was what Ezekiel (and other prophets) had prophesied. After the exile only a small remnant returned to Judah (Ezra 2:64–69), the rebuilding of the Second Temple under Zerubbabel was disappointing (Hag. 2:3) and the Zadokite priesthood functioned only until the rise of the Hasmoneans (c. 167 BC). This demonstrated that the post-exilic community had not experienced the physical aspects promised by the prophets for the restoration. In addition, the inability of the post-exilic community to find the fulfillment of the restoration spiritually was revealed by their repeated covenantal violations: those who returned to Judah continued to disobey the Mosaic law (see Ezra 9:1–2; 10:10–14: Neh. 5:1–10; 13:15–18; Zech. 1:4–8). These facts indicate that they were intended for fulfillment once the Messiah establishes theocratic rule under the new covenant (Ezek. 36:25–28; 37:26-28; Jer. 31:31–34) with national Israel in the Promised Land (Ezek. 37:21–22), which will result in renewal politically (Ezek. 34:23–25a; 37:24-25; Zech. 14:9, 16-17), materially (Ezek. 34:25b–29; 36:29-30, 37-38), and spiritually (Ezek. 34:30–31; 36:25-28, 33; 37:11-14).

Jewish tradition sought to give hope to the Jewish community over the obvious failure of their post-exilic ancestors saying God told Ezekiel that this would not be fulfilled at the return from Babylon (Jer. 27:22), but that the plan revealed to him would still affect a godly purpose. According to the Midrash: “Learning in the Bible about the description of My House is as great as the building of it. Go and tell the Jewish people to occupy themselves in learning about the Temple, and in that merit I will consider I as if they are actually involved in building it” (Yalkut Shimoni on Ezekiel 43:10-11).

Even the commentator cited previously who sought to place this prophecy’s fulfillment in the return of 538 B.C. and rebuilding of the Temple in 516 B.C. still postponed the fulfillment of chapter 47:1-12 to the time of the Messiah. Why should only this portion of the prophecy be considered as having its fulfillment in the messianic age? The same question must be posed to those who have thought that the form of government in these chapters reflects the religious polity of the restoration community under the Persian administration of Darius I.[31] This is unwarranted for in other prophetic texts this kind of restoration government is clearly reserved for the eschatological kingdom of Israel.[32]

If Ezekiel’s prophecies were meant to be fulfilled historically in the Second Temple they must be considered a failure. Any attempt to make the Second Temple fulfill these restoration prophecies force us to either abandon literal interpretation, which, as we have seen, the details of the text do not allow, or admit that the Word of God itself has failed, which orthodox theology cannot allow. For this reason Jewish interpreters concluded that the Second Temple was not built according to Ezekiel's plan because it was not yet the time to build this Temple. Rashi, one of the greatest Medieval Jewish commentators, explained this when he wrote:

The return to Israel in the days of Ezra could have been like the first time the Jewish people entered Israel in the days of Joshua …However, sin prevented this, for their repentance was imperfect. Since they were not worthy, they did not have permission to build the Temple which was designated as the Temple for the eternal redemption, for when it will be built according to this design, the [divine] glory will rest upon it forever.[33]

One objection to the eschatological interpretation of chapters 40-48 is the alleged absence of eschatological language such as “on that day,” “in the latter days,” which appear in chapters 34-37, and especially 38-39. However, as noted above, the literary linkage to these chapters establishes an eschatological setting as does the description of the transformations of the Land, city of Jerusalem, Temple, and priesthood from the past. The unprecedented change from the laws of the past, the return of the Glory of God (Ezekiel 43:1-12), the extended holiness of the Temple Mount, the physical changes in the Land of Israel (Ezekiel 47:1-12), the enlarged boundaries of the Land (Ezekiel 47:13-23), and God’s Presence dwelling in an enlarged Jerusalem (Ezekiel 48:35) all serve to indicate that the time of fulfillment is eschatological. This is especially seen when these details are compared with similar accounts of a future Temple, raised Temple Mount, and restored conditions in other prophetic books of the Old Testament, most of which do contain these eschatological time markers such as Isaiah 2:2-4; 56:6-7; 60:10-22; Jeremiah 3:16-17; 31:27-40; 33:14-18; Joel 3:18-21; Micah 4:1-8; Haggai 2:7-9; Zechariah 6:12-15; 14:16, 20-21. Specifically, we may categorize those related only to the Temple and its ceremonies as in the chart below. These demonstrate that Ezekiel’s prophecies related to Temple, priesthood and the sacrificial system were shared concepts related to fulfillment in Israel’s time of restoration. It is also evident that the Prophets read one another’s writings (since they were recorded divine revelation like their own) to learn and develop the revelation imparted to them (intertextuality).

When we consider the restoration of the Levitical priesthood in Ezekiel we find that it not only that other prophetical books agree, but that Ezekiel’s prophecy is the most complete statement of their fulfillment. In fact, the ancient promises to the Levitical priesthood have no literal fulfillment unless Ezekiel’s prophecy is eschatological. God promised to Zadok was the Aaronide high priest at the time of David and Solomon (1 Samuel 8:17; 15:24; 1 Kings 1:34; 1 Chronicles 12:29) and his descendants an everlasting priesthood (1 Samuel 2:35; 1 Kings 2:27, 35). This promise was the reconfirmation of similar promises made to Zadok’s ancestor Phinehas (Numbers 25:13), and Phinehas’ grandfather Aaron, the progenitor of the Israelite priesthood (Exodus 29:9; 40:15). The Zadokite priesthood was the dominate priesthood up until the time of the Maccabean revolt after which it was corrupted and replaced by political appointments to the priesthood under the Hasmonean dynasty. Thus, the last priests serving the Temple when it was last destroyed in A.D. 70 were not of the legitimate Zadokite line. Jewish sects like those at Qumran, who claimed to be Zadokite priests (1QS 5:2, 9; 1Qsa 1:2, 24; 2:3; 1Qsb 3:22), rejected the Jerusalem Temple and its priesthood and expected their priesthood to regain its position of service in a future Temple to be rebuilt after a climatic end time war in which the Hasmonean priests would be punished (1 QpHab 9:4-7; 4QpNah 1:11).[34] Only Ezekiel unequivocally provides the fulfillment of the promise to the sons of Zadok by making them the priests that serve the Millennial Temple (Ezekiel 40:46; 44:15). Ezekiel’s contemporary Jeremiah in his prophecy linked the perpetuity of the Levitical priesthood with the perpetuity of the Davidic dynasty and guarantees it by the perpetuity of the earth’s rotation on its axis (Jeremiah 33:17-22). If Ezekiel’s prophecy of a future Zadokite priesthood is spiritualized, then, according to the linkage in Jeremiah’s prophecy, the promises of the Davidic Covenant (2 Samuel 7:13, 16) could also be spiritualized. This would put all messianic fulfillment in jeopardy (including that fulfilled in Jesus)! Consequently, if we accept a literal and eschatological fulfillment for the Levitical priesthood we must also accept it for the Temple which they serve. In addition, if 12,000 can be sealed from the tribe of Levi during the Tribulation period (Revelation 7:7), then a literal restoration of the Levitical priesthood after the Tribulation is certainly plausible. Therefore, in harmony with other prophets, Ezekiel depicts an eschatological restoration of which the Temple and its priesthood are an essential part.

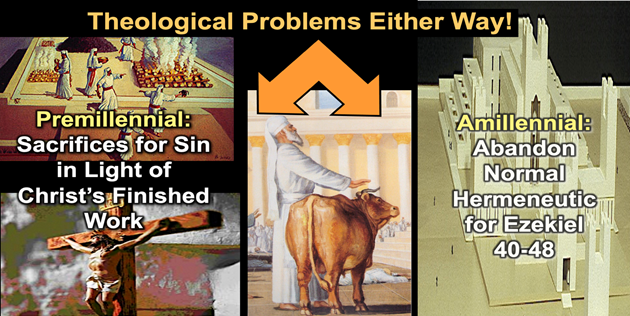

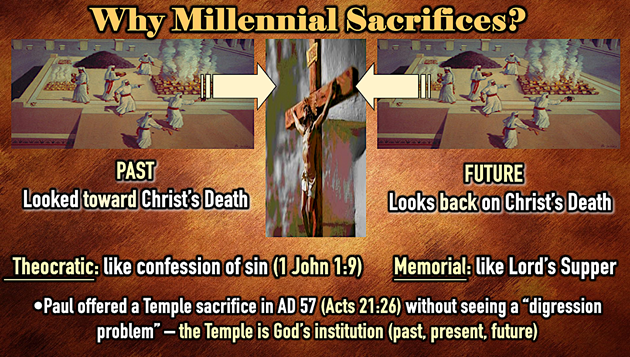

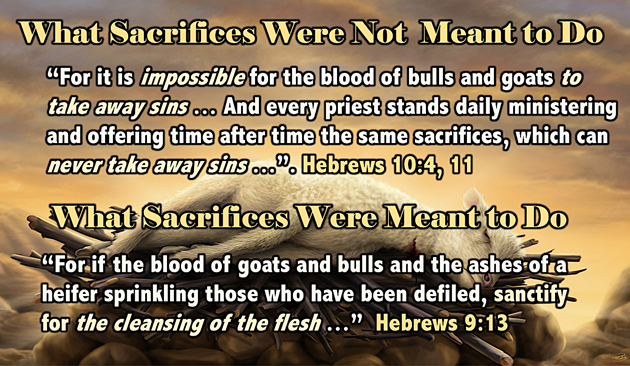

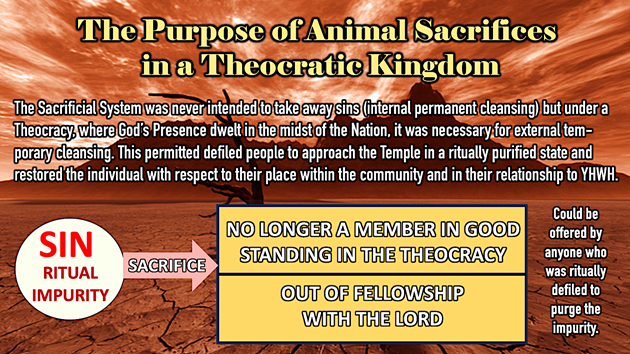

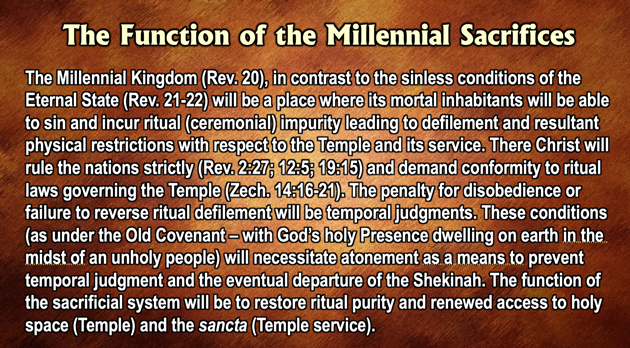

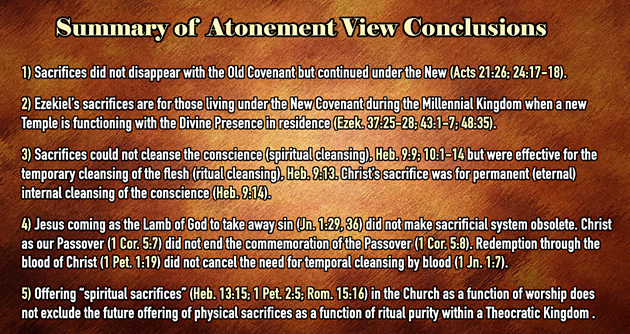

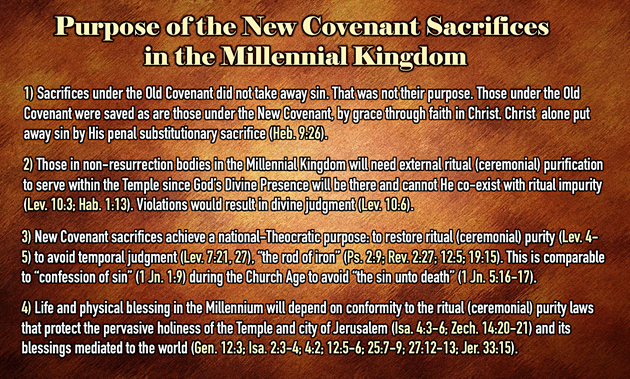

7) The Requirement of Sacrifices in Ezekiel’s Temple Requires a Literal Interpretation

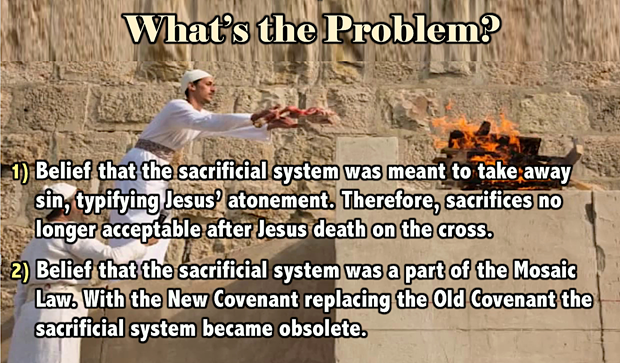

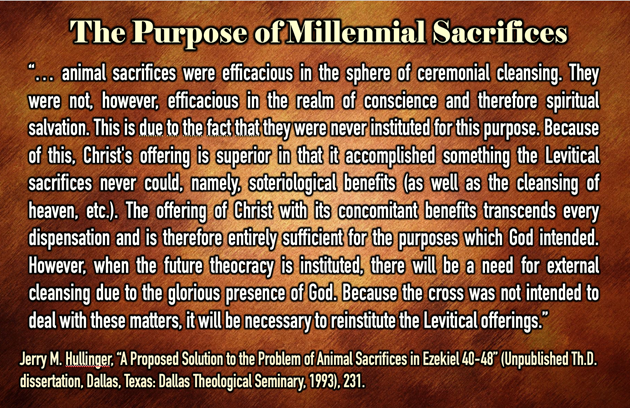

Reformed teachers argue against dispensationalism on the grounds that a literal interpretation of animal sacrifice in Ezekiel 40-48 is both contradictory to New Testament texts and theologically heretical. Reform scholars such as Oswalt Allis and Edmund Clowney call the view an embarrassment to the dispensationalist because “it requires the reestablishment of the Mosaic sacrifices and the Aaronic priesthood which, according to the Book of Hebrews, have ended.”[35] Former Dallas Theological Seminary student and Reformed scholar Keith Mathison expanded on this point in his study on Dispensationalism:

Dispensationalists understand Ezekiel 40-48 to be a prophecy of the future millennial temple and the worship that will occur there. The problem is that there are numerous passages in these chapters that depict the practice of animal sacrifices (40:38-43; 42:13; 43:18-27; 44:11, 27, 29; 45:13-25; 46:2-7, 11-15, 20). These verses should not be interpreted literally and placed in a future millennium. Hebrews 10:10-18 forbids it: “Now where there is forgiveness of these things, there is no longer any offering for sin” (v. 18). According to Hebrews the purpose of the sacrificial system has been fulfilled. The once-for-all sacrificial death of Christ has forever ended the offering of animal sacrifices. Some dispensationalists answer that these animal sacrifices will merely be memorials offered in remembrance of Christ’s death. But that is not what Ezekiel literally says. Ezekiel calls these offerings “sin offerings” (40:39; 43:19, 21, 22, 25; 44:27, 29; 45:17, 22, 23, 25; 46:20). And Hebrews 10:18 says that after Christ’s death there is no more offering for sin. Moreover, the offerings in Ezekiel 45:15, 17 are literally said to make atonement … It is impossible to interpret Ezekiel 40-48 in a strictly literal manner in reference to a future millennium without denying the clear teaching of Hebrews on the final sacrifice of Christ. To do so introduces a contradiction into Scripture …[36]

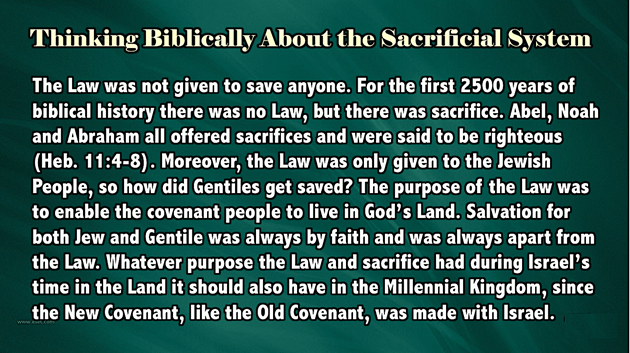

When the Temple was standing its most central function was as a site for sacrificial worship. Every Jew we read about in the Bible sacrificed, from Abraham, the father of the Jewish Nation, to Jesus, the founder of Christianity.[37] When the Temple was destroyed in A.D. 70 it brought a cessation to this sacrificial system for Judaism. Yet, despite this loss, Jewish liturgy preserved the ancient Temple services, recounting the sacrifices verbally in accord with the verse in Hosea (14:3): "So we shall render for bullocks the offering of our lips." In the words of the Talmud: "The prayers were instituted in correlation to the tamid sacrifices." The tamid, or olat ha-tamid was a twice-daily offering, morning and evening, of a male lamb. Yet, even though the sacrifices were continued in symbol, Jewish orthodoxy maintained the belief that they would return in substance with the Third Temple. This hope is clearly supported in Ezekiel’s prophecy of the Final Temple where detailed instructions concerning the priestly sacrificial service are elaborated.

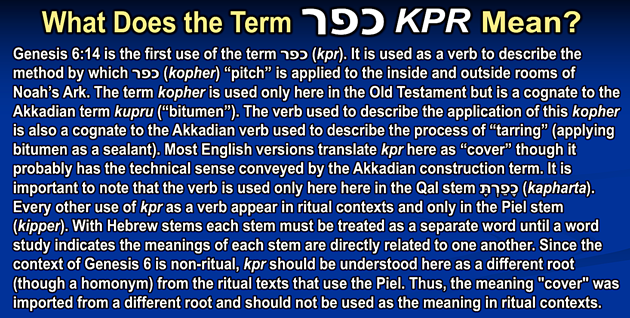

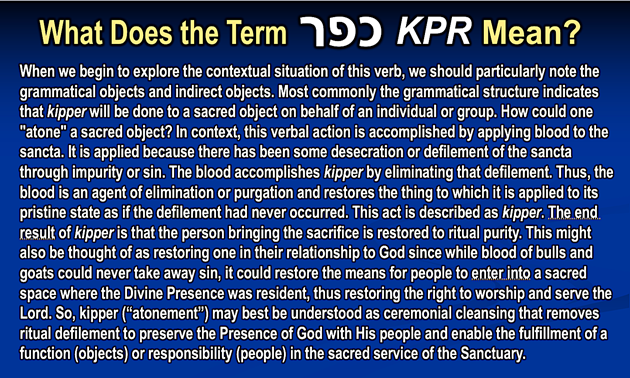

Every interpreter of the last chapters of Ezekiel must wrestle with the fact that out of these nine chapters there is a statement concerning the sacrificial system in every chapter but one (chapter 47). These references include: “new moons and sabbaths … all the appointed feasts” (Ezekiel 44:24; 45:17; 46:3, 11-12), “daily offerings” (Ezekiel 46:13-14), “burnt offerings, grain offerings, and the libations” (Ezekiel 45:17; 46:2, 4, 11-15), “blood sacrifices” (Ezekiel 43:20), an “altar” for burnt offering (Ezekiel 40:47; 43:13-27), an “altar” for incense offering (Ezekiel 41:22), “boiling places” to “boil the sacrifices of the people” (Ezekiel 46:23-24); a “Zadokite” priesthood to “offer Me the fat and the blood” (Ezekiel 40:46; 42:13-14: 43:19; 44:15-16; 48:11), a “Levitical” priesthood to “slaughter the burnt offering” (Ezekiel 44:10-11; 48:22). Furthermore, the offerings are stated to be for “a sin offering” (Ezekiel 43:22, 25; 44:24, 29) and to “make atonement” (Ezekiel 43:20; 45:25). Since the sacrifices and sacrificial personnel are so prominent throughout these chapters, the treatment of the sacrifices cannot be avoided as incidental.

Therefore, the first question that must be answered is whether these references to “sacrifice” are intended as symbol or substance? These options are not merely academic concerns but have significant theological implications. As the late German prophetic scholar Erich Sauer states: “We stand here really before an inescapable alternative: Either the prophet himself was mistaken in his expectation of a coming temple service, and his prophecy in the sense in which he himself meant it will never be fulfilled; or God, in the time of Messiah, will fulfill literally these prophecies of the temple according to their intended literal meaning. There is no other choice possible.”[38] However, the option most commonly resorted to by interpreters is to abandon a literal interpretation of all of Ezekiel’s prophecy in chapters 40-48 in preference of the symbolic. This is at least a consistent interpretation, since if spiritualize the sacrifices we must do the same for the Temple and with all the detailed promises of Israel’s restoration.

An example of the abandonment of literal fulfillment, on the basis of the supposed non-repetitive nature of the sacrificial system post-Jesus’ atoning sacrifice has been voiced by none other than a professor at a dispensational seminary:

The inclusion of so many minute details suggests that the temple described here will be a literal reality in the Jerusalem of the future (see Isa. 2:2–4; Hag. 2:9). However, the final sacrifice of Jesus Christ has made the Levitical system obsolete (see Heb. 9:1–10:18). To return to this system, with its sin offerings and such, would be a serious retrogression. Ezekiel’s audience would have found it impossible to conceive of a restored covenant community apart from the sacrificial system.132 Now that the fulfillment of the vision transcends that cultural context, we can expect it to be essentially fulfilled when the Israel of the future celebrates the redemptive work of their savior in their new temple. Ezekiel’s portrait of the Davidic king, or “prince,” is also contextualized to some degree. The king leads the community in worship and must even offer sacrifices for himself. Ezekiel also seems to anticipate the establishment of a dynastic succession (see 45:8; 46:16–18). Ezekiel’s audience would have found this portrayal quite natural. However, Jesus, the one who fulfills the vision, will have no need to offer such sacrifices, nor will he institute a dynasty. On the contrary, he will reign over his kingdom forever.[39]

The consistent literal school of interpretation is the only system able to interpret the references to sacrifice in a manner that is consistent with the uses of these terms throughout the Old Testament. Where else in the Old Testament is the priesthood, the altar, the feasts, the offerings, and the sacrifices made typical or symbolic of any other truth? If the New Testament is suggested as the key to interpret it symbolically, how did those Jews, for whom the book was written, interpret the book for over 600 years while waiting for this key? But even if the New Testament suggests a spiritual pattern for interpreting the sacrificial system, it provides no specific pattern that enables one to interpret the sacrificial references in Ezekiel. For this reason, there can be no consistent interpretation of this text by the symbolic method and therefore, no clear understanding of its message. Moreover, the symbolic approach has to deal not only with the references in Ezekiel, but with numerous other references to sacrifices within eschatological contexts (see, Isaiah 56:6-7; 60:7; 66:20-21; Jeremiah 33:18; Zechariah 14:16-21; Haggai 2:7; Malachi 1:11). For example, one of these in Jeremiah 33:17-23 prophesies: “For thus says the Lord, ‘David shall never lack a man to sit on the throne of the house of Israel; and the Levitical priests shall never lack a man before Me to offer burnt offerings, to burn grain offerings, and to prepare sacrifices continually … Thus says the Lord, ‘If you can break My covenant for the day, and My covenant for the night, so that day and night will not be at their appointed time, then My covenant may also be broken with David My servant that he shall not have a son to reign on his throne, and with the Levitical priests, My ministers, as the host of heaven cannot be measured, so I will multiply the descendants of David My servant and the Levites who minister to Me.” Can this prophecy be spiritualized to find fulfillment in David as Christ and the Levites as Christians? This is not possible because the fulfillment of the prophecy in Jesus depends upon a literal fulfillment as the “son of David” by physical lineage (see Matthew 1:1), which the symbolical school accepts. It would be hermeneutically inconsistent to take the prophecy to David literally and the prophecy to the Levites as spiritual, especially since they are bound together in a dual promise of perpetuity whose fulfillment is divinely guaranteed. Therefore in the same way the fulfillment of this prophecy for the Levites depends upon their being the physical descendants of Levi. To take this other than literally would be to remove it (in the case of David) from the rank of messianic prophecy, yet it is also obvious that to find a literal fulfillment in any time but the future would be to admit that this prophecy has failed. The fulfillment, then, must take place with Christ reigning on the throne of David in the Millennial Jerusalem and the Levites ministering through the sacrifices in a rebuilt Temple.

It is also remarkable, from the symbolic point of view, that the main passages dealing with the sacrifices in Ezekiel (the altar of burnt offerings, the priests and Levites, the sacrificial offerings) are introduced immediately after the Ezekiel 43:1-12 in which the Glory of God returns to the Temple Mount to restore its sanctity and bring an extended new spiritual dimension to Israel (verse 12). The contrast with the old defiled order is described in terms of there no longer being any of the former abominations in the Temple (verses 8-9), and it is only on the condition that Israel is truly “ashamed of all that they have done” (verses 10-11a) that the design of the Temple is to be made known and its statutes performed (verse 11b). If, according to the symbolic school, the old sacrificial system had truly been fulfilled by Christ’s sacrifice, which in the symbolic view would be represented by the coming of the glory of the Lord into the Temple, then why would sacrifice symbolically follow as part of this new design? By this interpretation it should have been part of the old order of abominations for which Israel should have been ashamed.